E-mail us

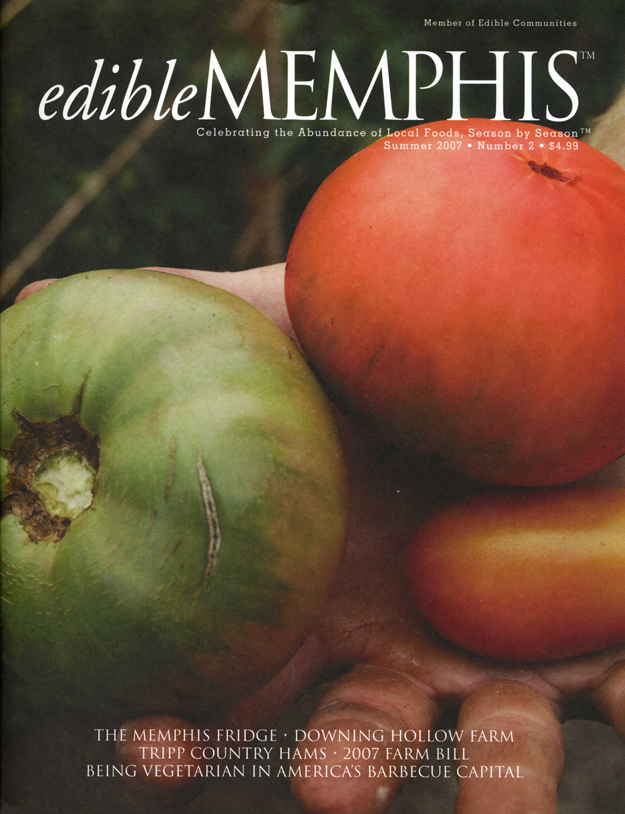

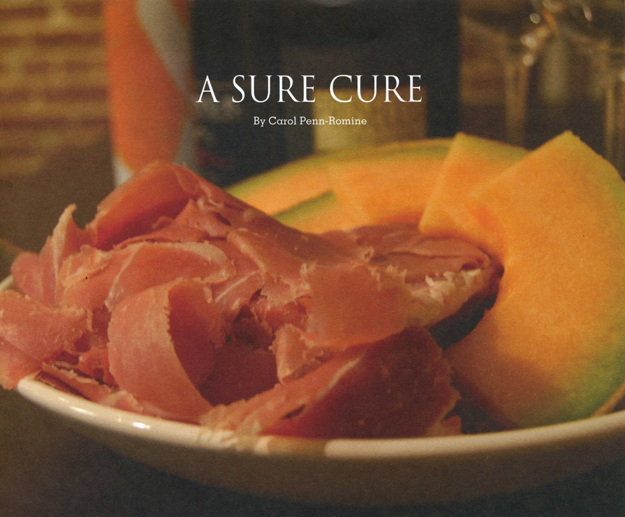

Shaved country ham with melon and prosecco

On a warm, sticky Sunday in June, some friends from the Memphis food community gathered to sample a country ham from west Tennessee, sliced paper-thin and served with melon.

We agreed that the ham was smooth, pleasantly porky and not too salty. All four wines we sampled with it, Prosecco, Cava, Malbec and Pinot Noir, complemented the ham nicely. None overpowered the ham, nor were they overpowered by it.

By the way, we ate the ham raw.

Yep, you read right. We did not cook it, because Mother Nature, using salt, smoke and time had, in her fashion, already cooked it for us.

There seems to be a disconnect between what Europeans and Americans do with their dry-cured pork. That lovely prosciutto you've had wrapped around a slice of melon in Tuscany or perhaps hugging a spear of asparagus at a party on this side of the Atlantic is in fact precisely the same thing as those country hams that are soaked, sliced thick and cooked to death here at home.

At this year's convention of the International Association of Culinary Professionals, I listened to Ari Weinzweig, CEO of the legendary Zingerman's in Ann Arbor, MI, make the case for treating American country ham the same as Europe's beloved dry-cured pork. As he explained that a properly cured country ham is as safe to eat uncooked as prosciutto, jamon iberico or any of its European counterparts, the inevitable question of food safety arose. Nathalee Dupree, goddess of Southern cuisine, chimed in that trichinosis was conquered in the United States decades ago. It may be a non-issue among most culi-narians, but try convincing someone of this who grew up in the days of cremate-your-pork-or-die-an-icky-death.

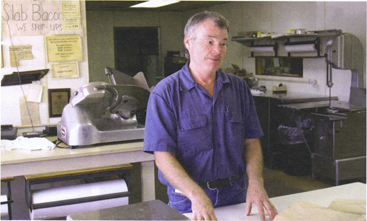

Left to right: Tripp Country Hams store front in Brownsville; Charlie Tripp; Tripp Bacon - deliciously cured with cinnamon and cayenne

The tendency in America is to take a country ham, soak it to remove the excess salt, rub it down with brown sugar or Coca-Cola and bake it or fry it until its as difficult to chew as a catcher's mitt. In fact, cooking the moisture out of a ham actually increases its saltiness. Such practices cheat diners of much of the ham's full range of flavors and textures.

Let's be clear—country ham is salted and dry cured, which removes the microbe-loving moisture, as opposed to city ham, which always involves moisture and requires cooking. You'd never want to eat city ham without cooking it first.

Curing pork was a method of food preservation in the days before refrigeration, long before it was considered a great way to turn out a tasty meal. And ham was originally smoked to keep the insects away. Nowadays, it's all about the flavor.

It takes 60 days in cold conditions for salt to penetrate pork sufficiently for it to be considered food-safe. This stage typically occurs during the chilliest time of year and is one reason for slaughtering hogs in the fall (the other being that by then their food supply traditionally had run out). After the salt stage, further aging in a hot environment and a little smoke are in order to produce the distinctive flavors that make country ham so very fine.

As with the production of wine and cheese, differences in climate, geography, ingredients and their handling are elements that make up something known as "terroir," and they all affect the flavor and texture of the final product. And as with balsamic vinegar, the extremes of hot summers and cold winters in which country ham cures are vital to a quality product.

So a friend and I cruised up to Brownsville to visit Tripp Country Hams and get the lowdown from the porkmaster himself, Charlie Tripp, who produces ham and bacon right in the middle of town. We hello'd a number of people who drifted into the shop for their weekly supply of bacon, sliced ham and unidentifiable chunks of meat and bone that can make a pot of vegetables sing, envying them the smalltown pleasure of going straight to the source for "the good stuff."

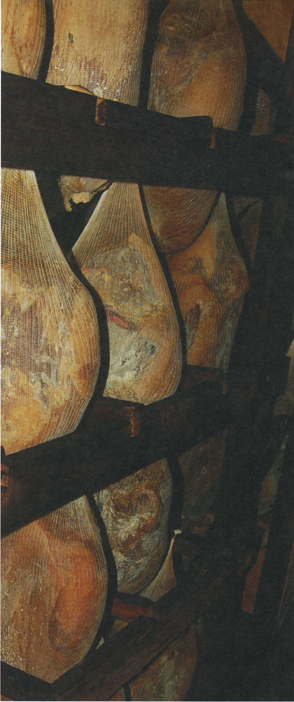

As Tripp explained the necessity of recreating winter and summer conditions indoors in order to produce country ham year round, we shivered in the room simulating winter, where mountains of ham rested under what looked like snowcaps of curing salt. Then we sweltered in the summer room where the ham hung in mesh bags and aged in a balmy 88 degrees.

These temperatures mimic the climate of the band of states running across the eastern U.S. from the Carolinas and Virginia through Tennessee and Kentucky and into southern Missouri, all of which produce quality country ham. It's the same climate as in the Po River Valley in Italy's Emilia-Romagna, where prosciutto and culatello are produced. Country ham requires seasons that are varied, but neither so hot as to rot the ham, nor so cold as to freeze it.

As for mold, this is a ham's badge of honor. In fact, it contributes flavor. A little mold ensures a delicate sweetness, a lot of mold, a wild edge. Leave it be until you're ready to eat the ham. Then just wash or trim the mold away.

The winter room - where thousands of hams

![]() spend

time packed in salt.

spend

time packed in salt.

Flavors and textures also vary with factors including the breed of the hog and what it eats. Virginia's Smithfield ham, for example, is produced from hogs that eat nothing but acorns. Other factors include length of curing time and the particular blend of curing seasonings, and the type of wood used for smoking. Tripp uses only hickory, as do most country ham producers in this region.

Such preservation makes the shelf life of a country ham practically unlimited, however Tripp advises not letting it age too long at home, since today's hams don't have the same copious layer of fat coating them as in times past. Fat helps prevent the meat from drying out, and a mere quarter-inch is insufficient to do the job of keeping a ham moist for years on end.

Incidentally, while American hog production has scaled back the amount of fat being bred into pork, Europeans have no qualms about it, as Weinzweig found when he attempted to shave extra fat off a ham while studying jamon production in Spain. "If you cut away any more fat I will have to kill you," his host warned.

Tripp said that while he receives orders for his ham from northeast-erners who plan to serve it prosciutto-style, there's not much call for it here at home. But there should be. Consider that prosciutto imported from Italy will set you back by about $20 a pound. A country ham costs about $2 a pound. This savings will help you invest in a meat slicer to shave the ham to its proper thinness!

![]() The

summer room - smelling of hickory smoke,

The

summer room - smelling of hickory smoke,

![]() the mesh-bagged hams hang in a balmy 88°

the mesh-bagged hams hang in a balmy 88°

Memphis' love affair with pork is evident, what with all the barbecue restaurants and contests. Fist fights break out over issues such as pulled pork or chopped, dry or wet, and shoulder or whole hog. We should expand our pork palate and enjoy the splendors of properly dry-cured pork that Mother Nature has pre-cooked for us.

As I traveled the back roads returning to Memphis, I took in an occasional deep breath, my clothes filling the car the smoky, porky splendor they'd absorbed during my visit at Tripp Country Hams. As the girls used to say about never washing their cheek after Paul McCartney had kissed it, I may never wash that shirt again!

Carol Penn-Romine grew up on a farm in northwest Tennessee and lived in Memphis for 15 years before moving to Los Angeles, where she is a chef writer and culinary tour guide. You can visit her company, Hungry Passport Culinary Adventures, at http://www.hungrypassport.com/

www.ediblememphis.com Summer 2007 / Edible Memphis